A Death in the Gunj is a movie that targets the patriarchy by seeing how toxic masculinity impacts the soft and gentle lead character, Shutu (Vikrant Massey).

Even though it is set in 1979, the host of characters is actually quite timeless.

So, just for fun, I thought it would be fun to draw parallels between the characters from the 70s and what their modern equivalents would look like.

Disclaimer: Do note that this is an exercise in fiction based largely on generalisations of modern demographics. This is not an attempt to pass judgment on any specific person or belief; it is merely an introspection of various social and cultural patterns of the past and the present.

Also, spoilers ahead!

A Death in the Gunj: Character Analysis

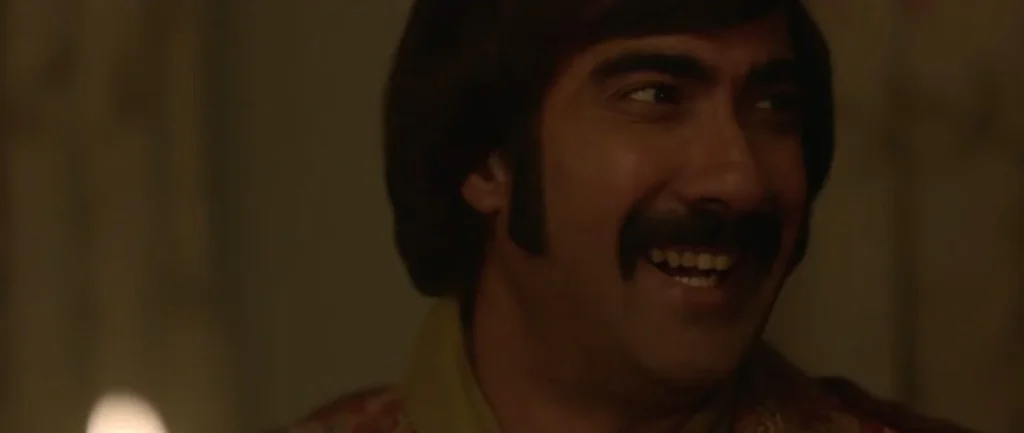

1. Vikram: Ranvir Shorey

Vikram, undoubtedly, is the “Alpha Male” of today’s day and age.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There are certainly men who are go-getters and work hard so they can call the shots. But as primatologist Frans de Waal (who is often credited with popularising the term itself) puts it, despite all animal groups having certain hierarchies, “An alpha male often can be a figure admired for empathy and protectiveness.”

Vikram is anything but that.

If Vikram existed today, he is likely to be the one tweeting about his many “accomplishments,” the biggest of which is being a defunct royal. One can also see him posting online about how men don’t women with high body counts for…clout.

Vikram is brash and abrasive and will go to any length to showcase his “strength” and “dominance,” something that is established in the Kabbadi scene that leaves Shutu with evident injuries to his face.

It is also likely that Vikram would not support the modern feminist movement for some shifty reason he must have gotten from social media. The way he treats both Mimi and, subsequently, his wife, is indicative of this.

In one of the first scenes in the movie, Vikram sleeps with Mimi despite having just gotten married. Then, there is the motorcycle scene in which Vikram rudely tells Mimi to get off his bike so he can go for a spin with Nandu instead. While one could argue there is nothing inherently wrong with Vikram’s request, his actions do warrant critique, given his drunken state and rude approach.

Another scene that stands out is when Vikram finally introduces his wife to his larger circle after they plead incessantly for her inclusion. At the dinner, she talks about the tradition of passing on gold anklets to the bahu of the house and talks up Vikram’s family—something that is, frankly, expected of her.

But then, when Vikram wipes his hands on his bride’s saree with blatant disregard, it becomes quite clear he isn’t a considerate or empathetic man. It also becomes that much clearer that if he cannot respect the woman he wants to spend the rest of his life with, there is no way he will extend any courtesy to Shutu, either.

2. Mimi: Kalki Koechlin

Kalki Koechlin has often been typecast in the “other woman” category of roles, be it in A Death in the Gunj or even Made in Heaven. As such, her performance as Mimi is not necessarily out of the ordinary for her, despite being spectacular.

If Mimi were a product of the technological revolution, one could certainly see her as some sort of a public figure, maybe as a content creator on YouTube. She’s got the style and panache for it, and she clearly couldn’t care less about what others think of her.

As a character, Mimi is also incredibly complex, especially if you wish to talk about her morality.

Initially, with how Vikram treats Mimi, it is incredibly difficult to not feel bad for her. But as she begins feeling jealous and dispensable, she repeats the cycle of toxicity by “using” Shutu as her rebound.

If “hurt people hurt people,” then Mimi is certainly guilty of inflicting the same pain on Shutu that was once inflicted on her. After all, her fling with Shutu leads to him developing feelings for her, but she carelessly brushes him aside after she is “done” with him.

In popular discourse, characters like Vikram are brushed off as “assholes” by the most well-intentioned people, but someone like Mimi would not receive such “kind” treatment en masse, even if they do practically the same things. In other words, it’s easier to ignore the actions of a man like Vikram because “he’s just another man,” but it’s much harder for most people to be as nonchalant about a character like Mimi due to various social and cultural expectations of what a “good” woman is.

Hence, a point worth pondering over here is, as author Roxane Gay of Bad Feminist puts it, if “we tend to hold feminism and feminists to unreasonable standards.”

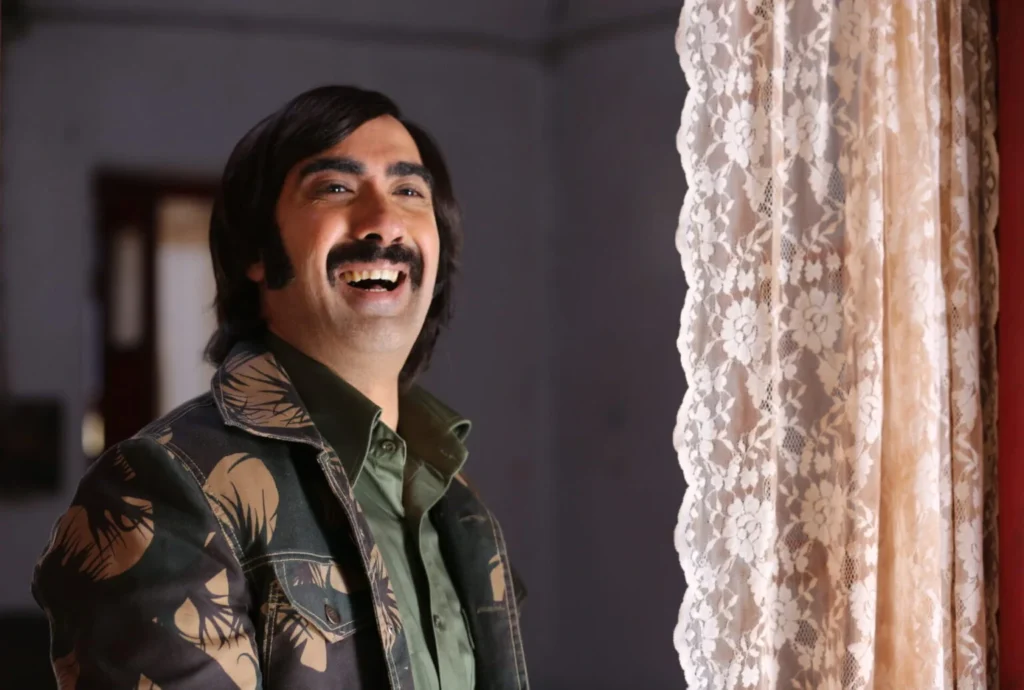

3. Nandu: Gulshan Devaiah

In today’s world, Nandu is likely to stand out as an “old-school” guy, the sort who just wants to do his job and look after his loved ones. Nandu is definitely going to be a guy loved by everyone. Someone dependable, someone worth looking up to, someone who embodies what “real men” are supposed to be.

However, upon closer inspection, it becomes clearer that Nandu would rather be in the good books of his fellow men than call them out when they cross the line. In other words, his defining quality is his inaction.

Something Theodore Roosevelt said comes to mind here:

The only man who never makes mistakes is the man who never does anything.

This quote, perhaps, best sums up Nandu, who is evidently the head of his family and yet never takes the call to prevent any form of harassment towards Shutu. Sometimes, Nandu even indulges in berating Shutu, especially when the latter is being used as the scapegoat for Tani’s disappearance.

Nandu is also the typical product of patriarchy. In Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, it is argued:

“If one takes patriarchal governments to be the institutions whereby half of the populace which is female is controlled by that half which is the male, then the principles of patriarchy appear to be two-fold: male shall dominate female, elder male shall dominate younger.”

Millett, Kate. Sexual Politics. 1st Ballantine Books ed. Ballantine, 1978.

As such, one could argue Nandu is someone who thinks he is doing the “right” thing by following the same norms and customs he was brought up with.

Moreover, Dr. Urvashi Sahni wrote for the American think tank Brookings:

“For boys to develop caring, nurturing dispositions, and perceive ways of caring other than being financial providers and protectors, they must first experience care themselves.”

And perhaps no other character in A Death in the Gunj is as good an example of this idea as Nandu. The scene in which he teaches Shutu how to drive also highlights the sentiment of the previous generations “having it worse” than the current generations.

Maybe things could have changed for Nandu after Shutu’s suicide, but it is more than likely that this is just another traumatic incident Nandu sweeps beneath the rug before moving on in his life, as indicated in the ending.

4. Bonnie: Tillotama Shome

If Bonnie were to exist today, she could very likely be like most Indian mothers who focus on childcare and domestic duties, thereby conforming to traditional gender roles. The only difference could be that she also has a career in addition to her domestic duties.

Bonnie, much like her husband Nandu, reminds me of a pacifist. But more than that, she is the character that truly embodies the idea of “women as agents of patriarchy.” The fact that she almost always calls out the “inappropriate” behaviour of Mimi (such as belittling the latter for cutting potatoes “wrong”) is interspersed throughout the film.

Also, Bonnie hardly ever stands up to her husband. This is seen when after their Kabaddi altercation, Bonnie tells him that Vikram should pick on people his own size, only for Nandu to steer the conversation to Shutu’s father’s fairly recent death. He even ends the conversation by saying that Shutu “needs to toughen up, and he take care of his mother now.” He then goes to away, with a stunned Bonnie saying, “Arre, but I just –“

In her Master’s thesis , Aparna Thomas (seemingly a professor with the Departments of Politics and Gender, Sexualities, and Women’s Studies at Cornell College) wrote:

“The ideology of “pativrata”, which literally means the “virtuous wife”, has dominated the lives of women in Indian society throughout history. It has also sustained the patriarchal structure which gave rise to this ideology in the first place.”

Thomas, Aparna, “Gender Consciousness, Patriarchy and the Indian Women’s Movement” (1996). Masters Theses. 4135.

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4135

While contending that assumptions and generalisations about both genders is at the heart of the Indian framework of marriage, she argues:

“The most important content of pativrata is the concept of the woman’s unfailing devotion to her husband.

…women were confined to the domestic or private world while the men took care of the outside or public world. This confinement of women to a private or domestic sphere is generally seen as controlling and further channeling power towards men.”

Thomas, Aparna, “Gender Consciousness, Patriarchy and the Indian Women’s Movement” (1996). Masters Theses. 4135.

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4135

This is very similar to the dynamic between Bonnie and Nandu, who got married at 23 and are now raising their child, Tani. Besides, for the most part, there is hardly any contention between the husband and wife. Things mostly run smoothly for them.

In other words, while Nandu is generally not “controlling” of his wife, one could argue he doesn’t really need to do much, given she is already artfully balancing all her domestic duties. (The idea that men should have the “right” to ascertain the duties of their wives or pass judgment on the same is a conversation for a different day, though it, too, reeks of the patriarchy).

But it is unlikely that Bonnie will break out of her societal shackles anytime soon. Circling back to the scene where Nandu angrily accuses Bonnie of not doing her “job” properly when their kid goes missing, Bonnie fights back and declares she isn’t the one who “didn’t do her job,” even Nandu’s mother (Tanuja) takes her son’s side in the argument.

Of course, emotions are running high as both parents likely imagine the worst outcome of the situation.

While no one holds Nandu responsible for Tani’s absence, Bonnie, too, isn’t taking the fall for it. She eventually puts the blame on Shutu, probably because it is the fastest path to her own absolvement. After all, women not doing everything perfectly (especially as mothers) is still pretty taboo in today’s world, despite the fact that their husbands are fathers too.

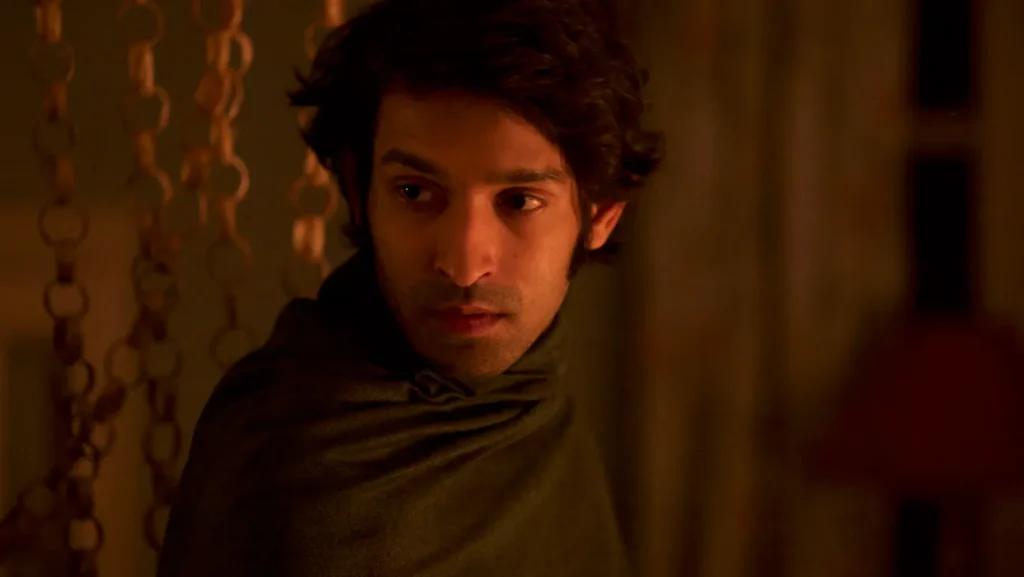

5. Shutu: Vikrant Massey

In today’s world, Shutu could likely be anyone–which is the scary part. He is still pretty young, hasn’t really kicked off his career yet, and resists indoctrinating himself with typical patriarchal ideology.

In other words, Shutu still thinks like a “boy” when the film begins, and A Death in the Gunj is the story of him “growing up” and coming face-to-face with the harsh realities of life.

In the one week he spends at McCluskieganj, Shutu bears the brunt of everyone else’s emotions.

Mimi says he “looks pretty” and uses him to rebound from Vikram. On the other hand, Vikram is always picking on Shutu and even gets really aggressive with him when the opportunity presents itself. Bonnie blames him for Tani’s disappearance, and as he sets out to find Tani, Nandu leaves Shutu behind with what appears to be a pretty blatant “can’t give a fuck” energy. Tani, who is just a child and is learning from the adults around her, gets cross with Shutu for leaving her behind and going out with Mimi instead.

Naturally, as his mental health deteriorates with each scene, it becomes clear Shutu is paying the cost for refusing to comply with patriarchal norms despite belonging to the gender that patriarchy is supposed to benefit. A case in point: Shutu’s name is also missing from the family trees (clearly foreshadowing the climax).

In other words, it becomes clear that even though patriarchy is a system built for men, those who don’t want to play by these rules pay an additional cost—sometimes, even their own lives.

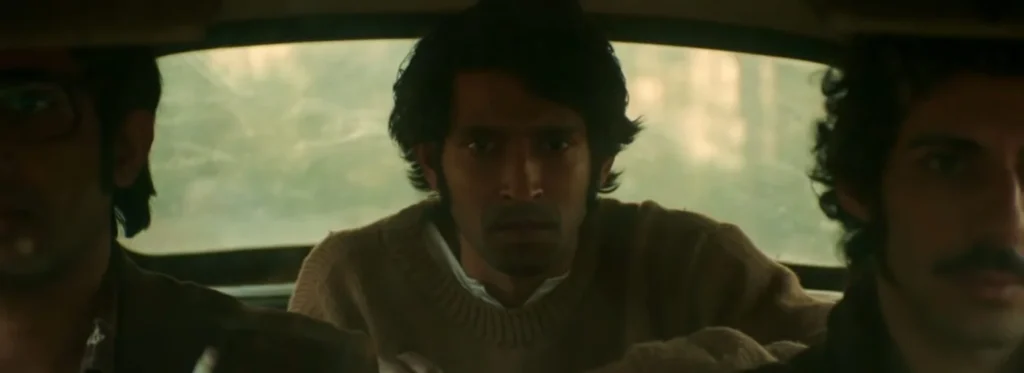

What is truly heartbreaking is revisiting the opening scene after learning about Shutu’s fate. A glance, a dialogue, and an act of posturing the corpse is all the time Brian (Jim Sarbh) and Nandu expend before getting rid of Shutu once and for all. Even Shutu’s ghost, shown in the car ride with them, is perplexed at the lax attitude of the men.

Hence, it becomes clear that there is no reverence or love lost for Shutu, even in his death, all because of his struggle to hold onto his own personality amid the patriarchal setup of society.