In the intricate tapestry of philosophical cinema, Ship of Theseus has stood out for its compelling story that challenges viewers to navigate the labyrinthine corridors of identity, ethics, and existence.

At the core of this cinematic gem lies an ending that reverberates with profound ambiguity, leaving much room for different interpretations and debates. Calling it an intellectually stimulating film isn’t wrong, but is there more to the script than meets the eye? Let’s discuss.

Consider yourself warned: SPOILERS AHEAD!

Table of Contents

But First… What is the Ship of Theseus Paradox?

Imagine you have a ship — let’s call it “Ship A”—and over time, some parts of it get old or break. So, you replace those parts with new ones.

At first, it’s still the same ship, right? There’s no evident reason to view it as a different entity despite the various changes it has undergone in terms of composition.

But what if you keep replacing parts, one by one, until every single part is new? Is it still the same ship you started with? Or is it a changed entity, i.e., “Ship B,” that constitutes something entirely different?

Is Ship A = Ship B?

Are the two even equivalent?

Which is now the “real” Ship of Theseus?

In an oversimplification, this is essentially the “Ship of Theseus” paradox.

It’s like asking if something can still be the same thing if all of its parts have been changed. Or, rather, how much change can something experience before its identity is also impacted?

Ship of Theseus Plot Overview

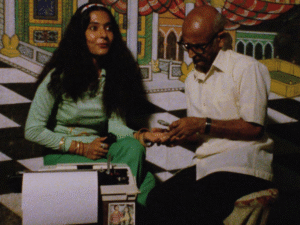

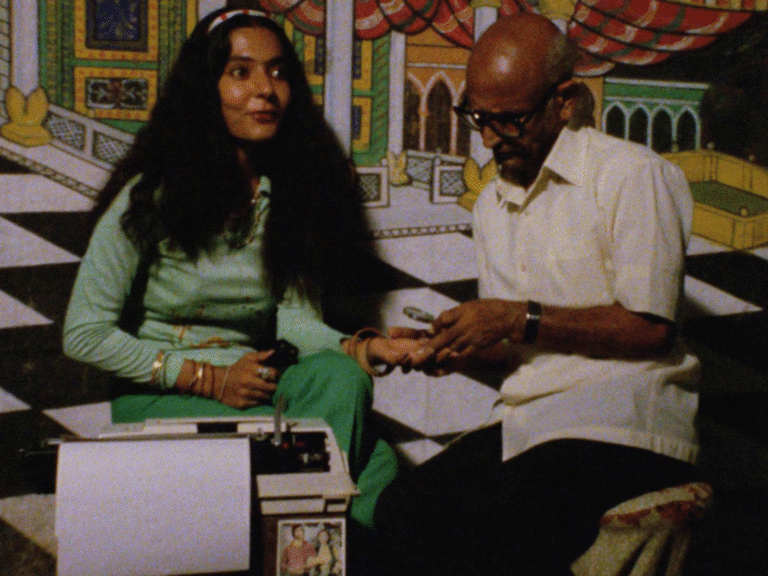

This Anand Gandhi venture focuses on three distinct people: a photographer named Aaliya, a monk who advocated for animal rights (Maitreya), and Navin, a charismatic stockbroker whose life takes an unexpected turn when he undergoes a kidney transplant.

As the three of them go through life and come face to face with some unexpected challenges, their entire notions of identity, virtues, morality, and interconnectedness in today’s world turn upside down.

Ship of Theseus Ending

There are three big patterns that stood out in the story to me:

- Each character has to make highly practical yet emotionally straining medical decisions, from eye surgery to a kidney transplant, implying that big life decisions are great catalysts for change.

- Their fundamental thinking about everything are challenged throughout their journey.

- What is right? What is wrong?

- How are we connected to the world?

- What does our existence even mean? (and so on…)

- With each character, the stakes get more intense, causing the audience to truly ponder over the circumstances and challenge their own preconceived notions.

So, with these two broad points in mind, let’s take a thorough look at each character’s individual story.

What Happens to Aaliya?

Aaliya, upon getting her eyesight back, but then she starts feeling like she is taking mediocre photos.

In a weird way, being blind was her superpower — at least in her head. She thinks it was because, not in spite, of her disability that people resonated with her art.

So, when she gets her sight back, she starts doubting her abilities, especially since she feels compelled to produce “better” photos now that she can see… only to get repeatedly (and obsessively) disappointed in herself.

A sort of madness takes over her, with her even wearing eye masks and blindfolds in a few scenes to recreate her previous state.

In an attempt to reconnect with her inner photographer, she travels to the mountains and tries to click more pictures. But when she sits on top of a stream and just enjoys the moment, she seems to have found what she was looking for.

As such, Aaliya has undergone significant change, both physically and emotionally, and has emerged with a different perception at the end of her ordeal.

Maybe before her surgery, photography was something she needed to interact with the world around her… to find out more about the nitty-gritty of things.

But now that she sees and processes things in a different manner, why would her photography style remain the same?

Moreover, will it truly even matter if this happens? Has change ever truly created a rift between an artist and their work?

Besides, what is the true nature of art?

Is it a coping mechanism or is it a way to mask feelings? If Aaliya’s photography changes a lot, does it mean it is no longer hers?

As you can see, all these questions that seem to be plaguing Aaliya are subjective yet very real.

Does Maitreya Die?

No, the monk — despite his many reservations and beliefs — does not end up dying despite almost knocking on heaven’s door.

Despite resigning to his fate, something makes Maitreya realise he is not ready to die at the last moment.

The last conversation Maitreya has with Charvaka is also very interesting, particularly because it beautifully challenges the argument for free will.

Charvaka talks about a particular type of fungus that can take over an ant’s sense of smell for the sake of food, shelter, and reproduction. The law student asks the monk if such a small spore can change the ant’s entire reality without the creature ever realising it, “How do you know where you end and where your environment begins?”

Then, when a devotee later asks Maitreya whether souls are real, the latter says he doesn’t know.

Hence, Maitreya seems to be questioning the “correctness” of his own beliefs. After all, the fact of the matter is that humans don’t know what they don’t know.

Although we live in the age of information, many often forget just how hard and challenging it has been for humans of generations past to amass and critically analyse information.

Even then, information is almost always relative to something (at least as far as the human experience is concerned). What might appear to be highly ethical in one context is almost barbaric in another, and that is the case with Maitreya.

From one angle, it is extremely commendable that Maitreya is willing to go to the lengths he is due to his huge grudge against the unethical pharma industry.

But should he really be sacrificing his own self to make a statement that will likely have no impact on the large, evil corporations?

Can he not do more when he is healthy and alive, like taking them to court and setting a certain precedent?

Should there not be an exception to the rule?

Maitreya is at a life-threatening crossroads, and only real medicine — made by the people he hates a lot — can save him. While he initially chooses to stand his ground and not compromise at all, he later understands and accepts that he is not ready to die.

Maybe, this whole time, Maitreya’s real fate was to live and continue his work, not sacrifice in vain. And had he never changed his mind, he would have never realised what he could even accomplish.

After all, who can concretely say if we do or do not have free will?

What Happens to Navin?

Fortunately for Navin, the kidney he received was not harvested from Shankar; it had actually been donated.

However, Shankar’s kidney was sold to a Swedish man for a heck of a lot of money. When questioned about taking advantage of Shankar’s poverty, the gora turns the table on them and starts talking about his own guilt instead.

In fact, the Swede initially makes a very self-victimising and irksome speech about the entire ordeal.

Personally, this particular story is just another reminder of how India has been looted and plundered in the past, and how the immense poverty that arose from colonialism still plagues our society in various updated forms today… but this is a conversation for another day.

Still, what the white man says is inherently correct — most people in such a life-or-death situation would have made a similar choice. And it really does seem like the guilt plagues him… but money is the ultimate answer to this issue.

As it turns out, the Swede man gives Shankar Rs. 6.5 lakhs, and even when Navin says they will go to court and get justice, more money, and his kidney, Shankar gets upset.

From a poor man’s perspective, it is not hard to see why Shankar would be willing to accept the Swede’s financial solution.

After all, for someone who has only ever seen hardships, getting financial stability seems to be more important for Shankar than getting his kidney back. And while most people may mock or challenge the ethical implications of his decisions, they likely won’t get why Shankar made the decision until they are in his shoes.

On the other hand, given that Navin is a stockbroker who can afford a lot more than Shankar as well as his recent kidney maladies, it makes sense that for Navin, health is more important than money.

So, anyone watching the Ship of Theseus gets immersed in this moral grey area that

Even Navin, for that matter, is frustrated with the outcome.

But his grandmom tells him that Shankar’s life is better today because Navin decided to take some action and at least try to right the wrongs in the world.

Sometimes, that is all one can do.

The Viewer is Also a Part of the “Ship of Theseus”

The film is all about furthering metaphysical philosophy and paradoxes that are abundant in life but are very difficult to deal with in reality.

As such, it seems the larger intent of Ship of Theseus is to truly impact its viewers, and what the audience goes through as the film progresses is truly where the spirit of the film lies.

Barring special circumstances, the one thing that will largely impact you after watching Ship of Theseus is its ideology and how it either aligns with — or contradicts — your own.

The story’s emotional depth allows you, the viewer, to undergo a philosophical metamorphosis as each scene bleeds into the next. Difficult thoughts and ideas compound, and towards the end, you’re left wondering about your own philosophy, your own worldviews, and your own reality.

Pay attention to how your thoughts evolve once you’re done watching this film.

Are you still the same person you were before you saw Ship of Theseus?

What is the Allegory of the Cave?

Imagine you’re imprisoned in a cave, along with other people. You can’t move your head to see behind/around you. Unbeknownst to you, there’s a bright light source (fire) behind you, and it makes shadows of things on the wall in front of you.

Initially, you are likely to feel that these shadows are the “real” deal because it’s all you’ve ever seen… It’s all you’ve ever known.

But now, for some reason, you have been released from the cave for the first time ever, exposing you to things like the sunlight and nature. Since your eyes are accustomed to the dark, they will hurt initially before they adjust to the sun.

However, once that pain subsides, you will see the glory of life and existence and, possibly, many other wonderful things that you weren’t able to do when you were shackled in the cave and did not know better.

What Does This Allegory Have to do With the Film?

The climax of Ship of Theseus shows us the donor leaving a cave, which indicates that he has “seen the light,” so to say, and how his beliefs have been shaped and moulded over his life. In death, it seems he acknowledges how “little” he knew.

We know the donor is dead, and we know that three other people have benefitted from his existence. Yet, we don’t know much else about this mysterious donor, and that’s okay.

What we do see is our three protagonists viewing this clip of the donor coming out of the cave, which serves to validate all the pain and anguish they have felt as they changed. Despite their reservations about art, life, medicine, animal rights, abuse, power dynamics, and whatnot, the three characters have also emerged from their ordeals.

They have reckoned with hard challenges that seem to have changed them on a very fundamental scale, so much so that existential dread has become commonplace.

Yet, watching the donor climb out of the cave and into the sunlight is a very poetic form of closure for them. Not only do the characters seem to realise that they are no longer the same person they were (at the beginning), but the allegory also works for those in the audience whom the story resonated with deeply enough to spark something…deeper in them.